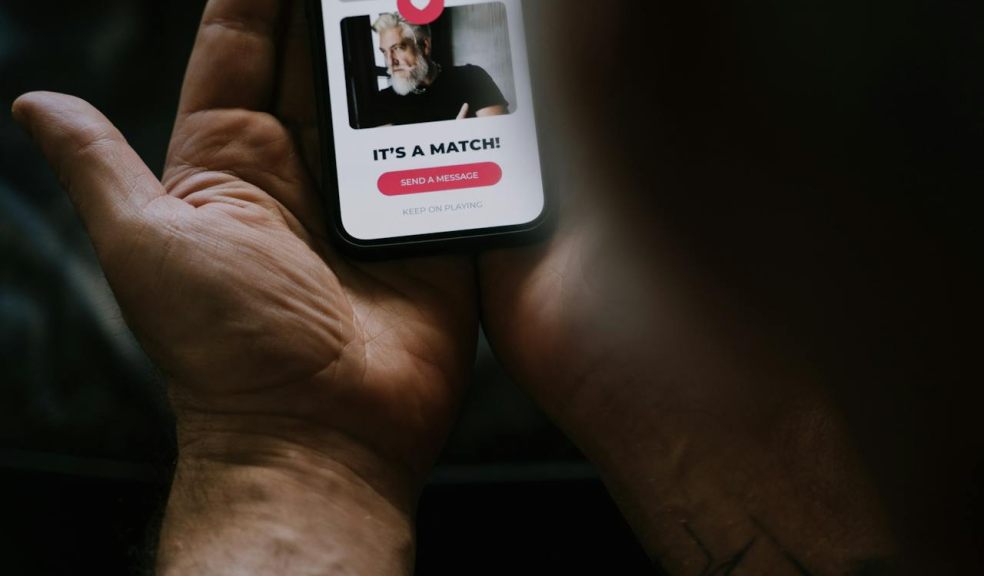

Are Dating Apps Going the Way of the Dodo?

Whitney Wolfe Herd built Bumble into a company worth billions. Her platform gave women control over the first message and reshaped how millions of people approached online romance. So when she told an audience that dating apps are "feeling like a thing of the past," people paid attention. The founder of one of the largest dating platforms in the world had openly questioned the future of her own industry.

The numbers behind her statement tell a familiar story to anyone watching tech stocks. Bumble's share price sat above $75 when the company went public. It now hovers around $8. Revenue dropped 10% in Q3 2025, landing at $246.2 million. Paying subscribers fell 16% to 3.6 million users. Tinder, owned by Match Group, reported 14.1 million paying users in Q2 2025, down 5% from the previous year.

These figures arrive alongside a quieter but more consequential trend. People are leaving their phones in their pockets and walking into rooms full of strangers again.

Swiping Loses Its Appeal

Burnout has become a defining problem for app-based dating. A Forbes Health survey from July 2025 found more than half of Gen Z reports feeling burned out "often or always" when using these platforms. The Kinsey Institute noted that only 21.2% of Gen Z relies on apps as their primary method for meeting people, while 58% prefer in-person encounters. These numbers point to a generation pulling back from the format that dominated the previous decade.

The fatigue extends beyond younger users. People exploring Tinder or Hinge alternatives often cite repetitive interactions and shallow matching systems as reasons to look elsewhere. Eventbrite data shows a surge in dating events since 2019, with speed dating and hobby-based meetups drawing singles away from their screens.

What Happened to the Promise

Dating apps sold convenience. Open your phone, see faces, swipe right, send a message, meet someone. The pitch made sense in 2012. Tinder launched that year and turned finding dates into something you could do on the bus or in line at the grocery store.

The model worked for a while. User bases grew. Subscriptions multiplied. Companies added premium tiers with extra features. But the product stayed fundamentally the same. You still looked at photos, read short bios, and hoped the person on the other end would respond.

After a decade of this, the format feels stale to many users. The same opening lines appear in thousands of inboxes. Conversations stall after a few exchanges. Matches accumulate but dates do not. The gap between matching and meeting someone has stretched into a chasm for a lot of people.

The Return of Real Rooms

Speed dating events have seen renewed interest since 2019, according to Eventbrite. Singles are showing up to hobby meetups, cooking classes, and group activities where phones stay in pockets. Organizers have started marketing "intentional dating" events, emphasizing meaningful offline connections over quick matches.

These gatherings work on different principles than apps. You see someone laugh in real time. You hear their voice. You notice how they treat the waiter or react when they spill their drink. Information flows faster and with more texture than any profile can provide.

The appeal is straightforward. Many people find it easier to evaluate chemistry when standing next to someone than when scrolling through their photos.

Revenue Models Under Pressure

Dating companies make money from subscriptions. Users pay monthly fees for features like unlimited swipes, read receipts, or the ability to see who liked their profile. This model depends on people staying on the platform long enough to pay.

If users leave out of frustration or find partners through other means, the subscription base shrinks. Bumble's paying user count dropped from 4.3 million to 3.6 million in a year. That represents hundreds of millions in potential annual revenue walking out the door.

Companies have responded by adding features. Bumble introduced modes for friendship and professional networking. Hinge marketed itself as the app "designed to be deleted." These adjustments have not reversed the downward trends in user numbers.

Who Still Uses Them

Apps have not vanished. Millions of people still swipe daily. Some meet partners this way. Others maintain profiles as one option among several.

The platforms serve specific purposes well. Someone new to a city can build a roster of potential dates faster through an app than through workplace introductions. People with unconventional schedules or niche interests can filter for compatibility before meeting. Those in rural areas sometimes find apps provide access to a dating pool that would otherwise be limited.

What Comes Next

Dating apps will likely survive in some form. The companies behind them have resources, user data, and brand recognition. They can adapt their products if they choose to.

But the dominant position these platforms held five years ago has eroded. Younger users show less enthusiasm for the format. Paying subscribers decline quarter over quarter. Founders openly discuss whether the model has run its course.

The Dodo went extinct because it could not adapt to new predators and changing conditions. Dating apps face their own pressures. People want something different from what these platforms currently offer.

Whether companies can build that something remains an open question. For now, the data points in one direction. Fewer people are paying, more people are burned out, and bars and meetup groups are filling with singles who would rather take their chances in person.