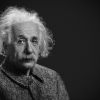

Of Lost Time to publish Letters of Note, including correspondence from Albert Einstein

Of Lost Time, Future Science Group’s literary unit, publishes letters of note in anthologies that provide insights into prominent historical moments and the lives of influential individuals. Now, in publishing personal correspondence by Albert Einstein, Of Lost Time allows readers a glimpse into the mind of one of history’s greatest and most influential figures.

Here, we’ll explore a letter from the German-born theoretical physicist to his young son Hans. This letter highlights the ways that Einstein attempted to bond with his son despite their distant relationship in the days before presenting his magnum opus, the general theory of relativity.

Einstein and Mileva Marić

Einstein is best known for his theory of relativity and his famous formula E=mc2, an equation that revolutionised the way that we understand mass and energy. Today, the name “Einstein” is synonymous with “genius.” But for all his intellectual brilliance, Einstein had a troubled romantic and family life.

In 1896, Einstein met Mileva Marić, his future wife and the mother of his two sons, Hans Albert and Eduard, at the Swiss Federal polytechnic school in Zürich. Early correspondence between the two revealed that the couple had a daughter, “Lieserl,” who was born in early 1902 but whose real name and fate are unknown. Einstein and Marić married in 1903. A letter that Einstein wrote later that year suggests that Marić gave the child up for adoption or that the infant died from scarlet fever.

The couple had their two sons in 1904 and 1910 while living in Switzerland. They moved to Berlin in 1914 but separated soon after. Marić had learned that Einstein held romantic feelings for his cousin, Elsa Löwenthal, and so she returned to Zürich, taking Hans and Eduard with her.

What’s more, previously uncovered letters of note, revealed in 2015, showed that Einstein had been communicating with an early sweetheart, Marie Winteler, while his wife was pregnant with Eduard.

Though living apart, Einstein and Marić remained married for five years until their formal divorce in 1919.

“My Dear Albert”

In November 1915, Einstein wrote to his eldest son, the then 11-year-old Hans. Just a few days later, the physicist would present his general theory of relativity to the Prussian Academy of Sciences, rocketing Einstein to global fame. This letter, written before the impending peak of Einstein’s career, reveals an anxious, estranged father, desperate to connect with a son from whom he had become physically and emotionally separated.

Einstein opened by expressing his pleasure, and perhaps relief, at receiving a message from his son: “Yesterday, I received your letter and was very happy with it. I was already afraid you wouldn’t write to me at all any more.” Einstein acknowledged that on his last visit to see his children in Zürich, Hans had told his father that he found the visit awkward. Keen to improve the situation, in his letter, Einstein suggested that they “get together in a different place, where nobody will interfere with our comfort.”

Whatever Hans’ decision, his father compounded the offer with a plea, urging that they spend a full month together every year. He hoped his son would see that he had a father who was “fond of you and who loves you.” He also explained that Hans could learn “many good and beautiful things” from him. Whether Einstein was alluding to his intellectual acumen, his position as Hans’ father, or both, he wrote that this learning was “something another cannot as easily offer.”

With striking self-awareness of his subsequent legacy, Einstein went on to hint at the wealth of knowledge he was about to bestow on the world, “achieved through such a lot of strenuous work.” According to Einstein, it wouldn’t only be the “strangers” of the world who would benefit from his achievements; the work was especially for his “own boys.” Einstein alluded to his imminent presentation of the theory of relativity, calling it “one of the most beautiful works of my life.” He promised Hans that “when you are bigger, I will tell you all about it.”

Learning Through Enjoyment

Einstein developed a love for music as a child. From the age of 13, with encouragement from his mother and a passion for Mozart, he studied the violin in earnest. In his later journals, he wrote that if he had not been a physicist he would “probably be a musician.” He described how he would often “think in music” and derived “most joy in life out of music.”

Much to Einstein’s delight, Hans also found “joy with the piano.” In the letter to his son, Einstein stated that music and carpentry are, in his opinion, the best pursuits for a boy of Hans’ age, “better even than school.” He encouraged Hans to play whatever pleased him, “even if the teacher does not assign those.”

Then, Einstein shared a statement that made this missive one of history’s great letters of note: “That is the way to learn the most, when you are doing something with such enjoyment that you don’t notice that the time passes.” Coming from one of the finest minds of all time, it’s a powerful piece of wisdom.

The Einstein Children

While the fate of Einstein’s daughter is unknown, his youngest son, Eduard, battled with mental illness, suffering a breakdown at age 20 and later receiving a diagnosis of schizophrenia. After his mother died, Eduard lived most of his adult life at a psychiatric clinic in Zürich, dying of a stroke when he was 55.

Of Einstein’s three children, Hans enjoyed the better fate. An engineer and educator who emigrated to the U.S. in 1938, he served as a long-time professor of Hydraulic Engineering at the University of California, Berkeley. More than a decade after his death, the American Society of Civil Engineers established the “Hans Albert Einstein Award” in 1988 to recognise those who have made significant contributions to the profession. The award continues annually to this day; its most recent winner is Subhasish Dey, a professor at the Indian Institute of Technology who has been widely recognised as a leader in sediment research, like the award’s namesake.

It appears that, despite a strained relationship, Hans heeded the words in his father’s letter, to throw himself into his pursuits so thoroughly so as not to notice the time pass. On Hans’ gravestone in Massachusetts stand the words: “A life devoted to his students, research, music and nature.”

Discovering Notable Correspondence

A non-profit organisation, Of Lost Time publishes historical letters of note that provide glimpses into key moments from history. Its carefully curated collections share personal correspondence from famous figures, such as Albert Einstein and Winston Churchill, as well as lesser-known writers. Each collection has valuable insights to share with readers. Thanks to these anthologies, Of Lost Time uncovers the lives and innermost thoughts of scientists, philosophers, artists, and everyday people, presenting fascinating windows into the past.

Alongside its collections, Of Lost Time provides further resources in the form of books and online articles. The non-profit also shares insights into selected letters through its video series “Letters for the Ages.” In these episodes, which are available to watch online, host Danny Al-Khafaji takes viewers on deeper dives into the minds of historical heavyweights like Galileo Galilei, Ludwig van Beethoven, and Van Gogh.